These questions mirror the ones raised by the eighteenth-century Scottish philosopher David Hume. Hume lived during the Enlightenment, a time in Europe when many believed that there is no need to believe in God or the supernatural. Hume’s argument against miracles is the most widely known argument against belief in miracles, and his argument is still used today, even though it is not nearly as strong as many think.

A key version of Hume’s argument is as follows: Natural Law is, by definition, a description of regular occurrences in nature. A miracle is, by definition, a rare occurrence. The evidence for the regular is always far greater than that for the rare. Since a wise person always bases his beliefs on that which has greater evidence, a wise person can never rationally believe in miracles.

Notice that this argument does not deny the possibility of miracles; it only claims that we are never rationally justified in believing a miracle claim because it is always more probable that a miracle did not happen than that it did. This, however, is not always the case. One problem with Hume’s argument is that it is not true that “the evidence for the regular is always greater than that for the rare.” For example, let us consider some rare events for which we clearly have good evidence. The origin of the universe is not a regular event, but we have good evidence that the universe began to exist. We do not regularly observe the origin of life from non-life (in fact we never have observed this), but we obviously know that life did come into existence. People are not regularly killed in Ford’s Theater. Planes are not regularly flown into skyscrapers. The winning Florida lottery number has never been 16-25-28-31-36 prior to 10/3/2011, but multiple media outlets confirm that this was the winning number on that day.

So clearly there can be good evidence for a rare event. The key is this: The rationality of believing that an event occurred (like a miracle) should be based upon all of the evidence supporting that event and not merely based on the rarity of the event. If someone says that some event is improbable, we must always ask: “Improbable relative to what supporting evidence?” If I have good enough supporting evidence for some rare event, then it is reasonable to believe that the event happened.

Another way to think of it is to say that we should consider the quality of evidence for miracles and not just the quantity of evidence. The quality of evidence (for example, from very trustworthy people who were eyewitnesses to an event) could “outweigh” the overwhelming quantity of reports by others who disagree, especially when those reports come from people who were not present at the time of the rare event.

One should also be careful about assuming that the so-called “natural laws” of science are unbreakable. Science can describe what regularly happens based on repeated observations, but it cannot prescribe what must happen or what cannot occur. That is, science, as science, cannot rule out miracles or exceptions to the norm.

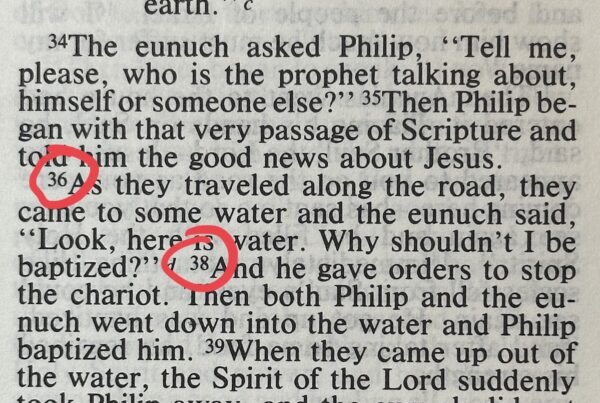

If God exists, then what we think of as “natural laws” are norms that were put in place by God. Yet God could choose to act outside (or beyond) those norms in a certain circumstance for a specific purpose. For example, as a norm, people do not rise from the dead. So the likelihood that Jesus rose from the dead seems to be zero, if the only evidence considered is how unusual it is to see dead people come back to life.

When you consider other relevant evidence (e.g., evidence that the Christian God exists, evidence for the empty tomb, the fulfilled prophecies about Jesus, evidence for the post-mortem appearances of Jesus, etc.), then our inference to the resurrection of Christ can become “the best explanation” available. In fact, it makes sense to think that God would particularly choose to raise Jesus from the dead because rising from the dead is perceived as outside the realm of human experience or possibility. By raising Jesus from the dead—clearly going beyond purely human possibility—God is validating the claims of Jesus regarding who He was and why He came.

-Zach Breitenbach, Director of the Worldview Center at Connection Pointe in Brownsburg, IN and the former Associate Director of Room For Doubt

One Comment