Jenni (from Michigan) submitted the following important and often-asked question:

How can the God of the Old Testament be the same God as the New Testament? The God in the OT commanded his people to commit genocide, killed little children, wiped out the entire world population in one fell swoop, sent plagues and devastation, and (if you believe the writers of the Bible) created a world full of people but decided to only reveal Himself and his rules to one group of people and condemn the rest because they were born in the wrong place. And then we are told in the NT that God is a God of love and mercy, that his followers are to spread peace and not hate, that we are to follow the example of Jesus who did nothing to stop his enemies from killing him. I am all for believing the New Testament record of Jesus and his followers, but how can anybody possibly believe God is “the same yesterday, today, and forever?”

Here are some considerations to help think through this issue.

Thanks for this very important question. Your overarching question is whether the biblical depiction of God in the Old Testament can be reconciled with the way God is described in the New Testament. Your concern is that in the Old Testament God seems harsh, judgmental, and even cruel, while God seems loving and compassionate in the New Testament. As part of this larger question, you have raised numerous specific concerns regarding the character of God in the Old Testament (e.g., God and genocide, God taking the life of children, etc.). These issues are significant enough that I could write a lengthy response to each one, but doing so is beyond the scope of this relatively brief reply to your larger question about the consistency of God throughout the Bible. So I will deal primarily with your main question after addressing your secondary concerns only briefly. I will, however, refer you to an excellent book by Paul Copan that deals in great depth with the specific issues you raised about God’s moral character in the Old Testament. The book is titled: Is God a Moral Monster?: Making Sense of the Old Testament God.

Without going into as much depth as Copan does on these issues, I would briefly suggest to you that God has not committed any moral atrocities in His stern punishment of sin in the Old Testament. With regard to God’s command to Israel to take over the land from the Canaanite nations living in the Promised Land, a little background information helps us to see that this should not be viewed as genocide. God revealed to Abraham in Genesis 15:12-21 that his descendants would possess the land that God had promised them, but God said that this would not happen for 400 years. God said that it would take that long before the sin of the people living in the land would become so horrible that God would have to judge them. So this command is in the context of God’s patient judgment against the sins of the Canaanites rather than God’s dislike for these people or His capricious desire to eliminate them. God waited until their sin had “reached its full measure” (Gen 15:16) before judging them. Moreover, as Copan argues in his book, it is not clear that non-combatants (women and children) were targeted when Israel took over the land. Copan makes a strongly-evidenced case that the language used in the Bible, which commands Israel to “totally destroy” the Canaanites, is not meant to include the killing of non-combatants. Copan gives multiple reasons for this in the book. It’s worth noting that, although the wicked nations around Israel would sometimes sacrifice their children to false gods such as Molek, God commanded Israel: “Do not give any of your children to be sacrificed to Molek” (Lev 18:21). There was a death penalty for disobeying this command (Lev 20:2-5), and it was condemned repeatedly in the Old Testament (Is 57:5; Jer 7:31; Ez 16:20-21). So God did not condone the killing of children in the Old Testament.

Just as driving the Canaanites out of the land was in the context of God’s judgment, the plagues against Egypt and the flood in which only Noah’s family survived were also in the context of God’s judgment against sin. They were not bloodthirsty acts in which God unjustly took the lives of people without a morally sufficient reason. Rather than an evil God who takes pleasure in causing death and destruction, what we see is a perfectly holy God who judges sin strictly.

With that being said, let’s return to your primary question. Does the Old Testament describe a God who is judgmental and strict but not loving and compassionate? Does the New Testament describe a God who is full of love and compassion, but lacks the firm judgment against sin seen in the Old Testament? To gain perspective on this, it is helpful to step back and look carefully to see if God’s love and compassion as well as His justice and judgment are clearly seen in both testaments. When we do this, I think we see that they are. Consider first God’s love and compassion for all people in the Old Testament. As already noted, God held off for 400 years and allowed the Israelites to remain in bondage in Egypt before bringing them into the Promised Land because the Canaanites were not yet fully corrupt and ready for judgment. God cared very much for these Gentiles and gave them as much time as possible to repent of their sins and avoid judgment. As another example, God sent Jonah to Nineveh (these people were not Jewish) because He did not want to have to bring judgment on them for their sins. God was concerned because they didn’t “know their right hand from their left” (Jonah 4:11). In other words, they were confused, sinful, and needed to repent. God also has a caring and personal relationship with non-Jews in the Old Testament, as seen by God’s interaction with Job. The character of God in the Old Testament is so compassionate that Ezekial writes: “As I live, says the Lord, I have no pleasure in the death of the wicked, but that the wicked turn from his way and live” (Ez 33:11).

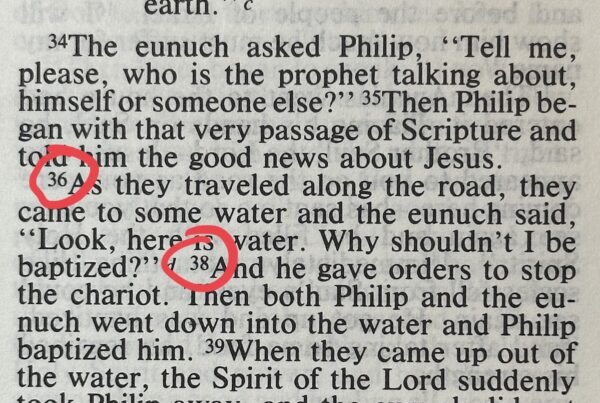

Just as God shows love and compassion in the Old Testament, He also demonstrates strict judgment of sin in the New Testament. Let’s just look at a few examples. Consider what God did in Acts 5 when Ananias and Sapphira boldly lied to God about their offering. God judged their sin, and they both died for what they did. As another example, Jesus—who is God in the flesh—was outraged at the money changers and those conducting business at the temple. He overturned their tables, drove them away, and scolded them for their sin. God struck down Herod for his sin in Acts 12:19-23, and he was eaten by worms. God also judged Elymas in Acts 13:4-12 by blinding him when he opposed God and tried to turn others away from God. So, although God is a God of love, grace, and compassion, He clearly does not hesitate to judge sin with severe consequences in the New Testament. Perhaps the supreme example of God’s wrath against sin in the New Testament is the price Jesus had to pay on the cross to bear our sins. At the cross, the love God has for us is clearly seen, but so is His wrath against sin.

So I hope this helps you to see that God’s qualities are consistent throughout the Bible. In both testaments, God is a God of incredible love and compassion; however, God is equally a God of justice and righteous wrath against sin throughout Scripture.

For more on this important topic of God being both loving and just, see the response to the question, “If God is loving, how could He condemn people to an eternity in hell?“.

–Zach Breitenbach, Director of the Worldview Center at Connection Pointe in Brownsburg, IN and the former Associate Director of Room For Doubt.

One Comment